Introduction

Welcome to Walpole, New Hampshire—a village whose quiet streets and dignified buildings offer one of the most intact windows into the aspirations of early nineteenth-century New England. As you begin this walking tour, you’ll notice a recurring architectural language: bold pediments, columned porticos, crisp white façades, white clapboard siding and simple, harmonious proportions. These are the hallmarks of Greek Revival architecture, the style that flourished in the United States during the early decades of the 1800s and shaped Walpole’s appearance at the moment when the town was entering its greatest era of prosperity.

In communities across New England, Greek Revival architecture embodied far more than decorative taste; it expressed the values and ambitions of a young republic. Americans looked to ancient Greece as the birthplace of democracy, and in adopting its forms they aligned their civic buildings, churches, and homes with ideals of self-governance, rational order, and integrity. In Walpole, this architectural vocabulary helped signal the town’s confidence in its future and its belief in the virtues of citizenship, learning, and public life. These same ideals also shaped the intellectual currents of the era, ideas that would later prompt New Englanders to look beyond institutions and outward forms, toward nature, conscience, and the inner life, themes we will return to at the close of this tour.

The Greek Revival style also marked a moment when the United States sought to define its own cultural identity. By choosing Greek prototypes instead of British ones, towns like Walpole expressed a compelling desire for independence and cultural maturity. The crisp geometry and restrained ornament that characterize so many of the village’s buildings announce a community grounded in order, stability, and enlightened aspirations. Yet even as Walpole embraced these rational forms, New England’s landscape—its rivers, fields, and distant mountains—remained a powerful source of meaning alongside the built environment. These are qualities that appealed strongly to New England towns engaged in trade, agriculture and civic improvement.

At the same time, Greek Revival’s adaptability made it ideal for the expanding settlements of the Connecticut River Valley. Builders could translate its clear forms into everything from grand meetinghouses to modest dwellings, giving Walpole a unified visual character that has endured for nearly two centuries. As we walk through the village, you’ll see how this style contributed to Walpole’s distinct sense of place: a village where democratic ideals are expressed in everyday buildings, where simplicity creates beauty, and where the architecture mirrors New England’s long history of community life, public responsibility and cultural ambition.

On this tour you will encounter a range of architectural styles, among them the earlier, more formal Georgian and Federal styles, and the later Romantic expressions of the Italianate, Gothic and Queen Anne styles. Each contributes its own chapter to Walpole’s architectural story. Yet despite these variations, the village’s overall character remains firmly rooted in the Greek Revival. Its clean lines, balanced proportions, and democratic symbolism form the prevailing visual language of the streetscape, giving Walpole a remarkable sense of cohesion even as individual buildings reflect changing tastes over time.

This tour highlights not only individual buildings, but also the people whose lives, beliefs, and aspirations they embody, revealing how architecture, landscape, and ideas together shaped Walpole’s enduring character. We hope you will appreciate how Greek Revival ideals helped shape Walpole into one of the region’s most charming and historically significant villages.

The first paragraph of each listing provides a brief summary of the site and its significance, with more detailed information in the following paragraphs for those who wish to explore further. If pressed for time during your tour, the first paragraph provides the essentials.

20 Westminster Street — Aaron P. Howland House

Built in 1834 by master craftsman Aaron P. Howland, this distinguished brick residence is one of Walpole’s finest expressions of Greek Revival architecture. Its prominent siting near the junction of Westminster Street and Main Street places it at the historic crossroads of the village’s transportation, commerce, and civic life. Architectural details inspired by Asher Benjamin, most notably the pedimented façade with a Palladian window, reflect Howland’s skill and the ambitions of early nineteenth-century Walpole. Later owners, including stagecoach entrepreneur Otis Bardwell, former owner Jennie Spaulding, and preservationist Guy H. Bemis, link the house to successive chapters of the town’s economic, social, and preservation history.

The Aaron P. Howland House, built in 1834 by master craftsman Aaron P. Howland (1801–1867), is among the most architecturally distinguished residences in Walpole. Standing near the meeting point of Westminster Street and Turnpike Road (now Main Street), the two oldest and most important transportation corridors in the village, the house occupies a strategic position in Walpole’s early street network. The house is not simply a refined example of Greek Revival design; it is also a material testament to Walpole’s role as a crossroads community shaped by travel, commerce, and the flow of ideas through the Connecticut River Valley.

Long before the house existed, its site occupied a strategic position within Walpole’s early street network. Westminster Street led directly to one of the region’s earliest bridges across the Connecticut River (built in 1807), which was a critical eighteenth-century crossing that linked New Hampshire with Vermont and with trade routes leading deep into western New England and New York. Main Street, originally the Charlestown–Walpole Turnpike, carried steady north–south traffic through the growing village. For a brief period Westminster Street was also known as Depot Street, because it led directly from the village to the railroad depot and railyard by the Connecticut River (built circa 1849), a reminder of Walpole’s important mid-nineteenth-century rail connections and of how successive transportation technologies reshaped the same civic landscape.

These roads formed the crossroads of the commercial and civic heart of Walpole. By the 1830s, when Aaron P. Howland erected his elegant brick dwelling just steps from their convergence, the village had become a minor regional hub, supporting stage lines, taverns, small industries, and a concentration of professional and civic life. The Howland House emerged from this context: a refined brick landmark rising along the same transportation network that would later shape the fortunes of some of its most prominent owners.

Howland’s craftsmanship is unmistakable. The warm Connecticut River Valley brick provides the backdrop for a façade grounded in the principles of the Greek Revival, then at the height of fashion. Like many skilled builders of his generation, Howland drew inspiration from the pattern books of Asher Benjamin, whose architectural guides democratized classical design for American towns and helped translate abstract civic ideals into everyday buildings.

The front-gabled façade is crowned by a bold pediment enclosing a Palladian window, a design flourish that appears again in several other Howland-attributed houses across Walpole. The main entrance, framed by fluted pilasters and a transom with sidelights, a detail echoed in the nearby William Buffum House, further cementing Howland’s stylistic fingerprint.

Inside, the house retains original random-width floors, crisp moldings, and folding interior shutters in the parlors and stair hall—features both practical and elegant. Fireplaces equipped with perforated heating tubes illustrate early experimentation with improved home heating in the decades before central furnaces.

Howland sold the house in 1842 to Anson Dale (1798-1853), who made a fortune in the California gold-fields and later lost it by speculating in Cheshire Railroad stock. His tumultuous career reflects the volatility of mid-nineteenth-century ventures that touched even small New England towns. His story underscores how even refined houses like this one were enmeshed in the risks and opportunities of a rapidly changing national economy.

The next owner, Otis Bardwell (1792–1871), ties the house directly to Walpole’s transportation economy—an economy shaped by the very roads that passed its door. Before purchasing the Howland House, Bardwell had lived for 25 years in the “Historic House” at 11 Old North Main Street, Walpole’s oldest surviving dwelling. During that period, he prospered as a stagecoach operator, eventually becoming the proprietor of several major stage and mail lines serving the Connecticut River Valley. His livelihood depended on the infrastructure of Main Street and Westminster Street, whose steady flow of passengers, mail, and freight made Walpole an important node in regional travel before the arrival of railroads.

Bardwell’s later roles as the first president of the Walpole Savings Bank and as an administrator of local trusts cemented his place among Walpole’s civic leaders. His ownership gives the Howland House a direct connection to the era when movement, communication, and enterprise shaped village life.

The property next passed from Bardwell’s heirs to Alfred W. Burt (1817-1891), a cabinetmaker, and later to his son George F. Burt (1852-1915), whose heirs sold it in 1895 to Jennie M. Spaulding (1863–1929). The deed conveyed ownership solely to Jennie, an uncommon assertion of women’s property rights at a time when married women were still navigating restrictive legal norms.

During the ownership of Jennie and her husband Frank A. Spaulding, the house took on its early-twentieth-century appearance. Around 1900, they added the broad Victorian portico that now spans the front façade. Rather than discarding Howland’s original entrance columns, the Spauldings moved them to a side porch, preserving a tangible link to the house’s first architectural moment. The side porch has since been re-built and the old columns are now in storage in the barn loft, awaiting their next chapter as a planned garden feature.

Jennie and Frank’s son Russell S. Spaulding inherited the residence, demonstrating a continuity of stewardship into the early twentieth-century.

In 1938, the house entered a new phase when it was purchased by Guy H. Bemis (1900–1996) and Marion K. Bemis (1907–1991). Widely known as “Mr. Walpole,” Bemis devoted much of his life to documenting and preserving the village’s architectural heritage. That the Howland House remained so intact into the late twentieth-century is due in no small part to the Bemises’ careful and appreciative occupancy. Their tenure connects the house to Walpole’s modern preservation movement and to the twentieth-century effort to value history as a foundation for community identity.

Why This House Matters: A Microcosm of Walpole’s History

The Aaron P. Howland House is far more than an elegant Greek Revival dwelling. It stands at the intersection—literally and figuratively—of nearly two centuries of Walpole’s evolution.

- Its architecture embodies the ambitions of early nineteenth-century America, grounded in classical ideals adapted for a growing New England village.

- Its location, near the junction of Westminster Street and Main Street, ties it to the transportation network that shaped Walpole’s prosperity, from early river crossings to bustling turnpike traffic.

- Under Otis Bardwell, the house becomes part of the story of stage lines, mail routes, banking, and the vibrant pre-railroad economy of the Connecticut River Valley.

- Under Jennie Spaulding, the house reflects shifting social norms and the expanding role of women as independent property holders.

- Under Guy Bemis, the property becomes a touchstone of community memory and architectural preservation.

These layers make 20 Westminster Street one of the most richly contextualized historic homes in Walpole. It offers not only architectural beauty but also a window into the lived experiences, ambitions, and economic forces that shaped the village from the 1760s through the twenty-first-century. It stands as a natural starting point for understanding Walpole as a community: how it grew, how it prospered, and how its residents have continually valued and preserved the built environment of their shared past. Together, these layers establish a foundation of civic confidence and public life upon which later generations would reflect more deeply on memory, meaning, and place.

Walk East on Westminster Street to see the Business District

In the early nineteenth century, much of the block where the Aaron P. Howland House now stands was part of a large tract owned by Dr. Ebenezer and Esther Crafts Morse, spanning most of the area bounded by Main, Turnpike, Elm and Westminster Streets. They sold the property, minus a few existing lots, to Nathaniel Holland, who operated a tavern on the site. Holland’s tavern property, including its buildings and roughly three acres, was sold to George Huntington in 1833, who continued the tavern operation and began subdividing the land. His sales of house lots along Westminster Street and north of the tavern on Main Street created the parcels that would eventually host 20, 16, 14, 10, and 8 Westminster Street. These subdivisions established the neighborhood that would later include the Aaron P. Howland House.

In the early nineteenth-century, much of the block on which the Aaron P. Howland House stands was part of an extensive tract owned by Dr. Ebenezer Morse (1785–1863) and his wife, Esther Crafts Morse (1791–1879). The Morses were prominent early residents, and part of their landholdings encompassed nearly the entire area bounded by Main Street, Turnpike Road (the diagonal section of today’s Main Street), Elm Street, and Westminster Street.

They sold this large parcel, minus the previously established Christopher Lincoln lot on the north and the Stephen Rice and Susan Bellows Robeson lots along Elm Street, to Nathaniel Holland (1788–1835). The original tavern on the premises was owned by John Crafts about 1793; Nathaniel Holland next operated the tavern, and the deed from the Morses to Holland describes the transfer as including the “buildings thereon,” specifically noting that the property was “the same premises Holland now occupies as a tavern,” amounting to about three acres. The only exclusion was an existing lease for the installation and maintenance of hay scales, a standard feature for weighing loads in a community centered around agriculture and transport.

In 1833, Holland sold the tavern property to George Huntington, who continued to run the tavern stand. At that time, the tavern faced Main Street on the site now occupied by the Irving Oil gas station. Huntington soon began subdividing the land, selling off lots both along Westminster Street and to the north of the tavern on Main Street. These subdivisions created the house sites we know today at 20, 16, 14, 10, and 8 Westminster Street, laying the groundwork for the neighborhood that would grow up around the future Aaron P. Howland House.

16 Westminster Street — Griswold Place

Built around 1834 for tailor Jonathan Weymouth, this refined brick house is a close architectural companion to the neighboring Aaron P. Howland House and is widely attributed to Howland’s hand. Its pedimented front gable with a Palladian window, along with its balanced proportions and restrained Greek Revival detailing, reflects the ambitions of the inhabitants of early nineteenth-century Walpole. Later known as the Rodney Wing House and today as Griswold Place, the building has adapted to changing uses, including service as an annex to the Walpole Inn during the town’s heyday as a regional destination. Now owned by The Walpole Foundation, it continues to serve the community while preserving the historic character of Westminster Street.

Just east of the Aaron P. Howland House stands 16 Westminster Street, identified in the 1959 Historic American Buildings Survey as the Rodney Wing House. At the time of the survey, the house was owned by Chester R. Wing (1900-1984), but today it is known as Griswold Place, in honor of Henry Griswold (1833-1889), who acquired the property in 1874. The house was built around 1834 for Jonathan Weymouth, a tailor, one of the skilled tradespeople who shaped Walpole’s early nineteenth-century village economy.

Although no builder is documented, the house is almost certainly the work of master builder Aaron P. Howland. Its architectural kinship to 20 Westminster Street next door is unmistakable. The most distinctive feature is the Palladian window set within a pediment-like front gable, a trademark element of Howland’s Walpole houses. The clean brickwork, classical proportions, and restrained Greek Revival detailing further reinforce the connection to the village’s mid-1830s building surge.

Over the decades, the property passed through numerous owners, adapting to community needs. In the early twentieth-century it served as an annex to The Walpole Inn, the large hotel that once stood across the street at 11 Westminster Street (demolished in 1962). During this period, the house provided additional lodging for visitors, supporting the busy hospitality trade that helped make Walpole a favored regional destination along Connecticut Valley transportation routes.

The house has been converted into a mixed-use structure (offices and apartments) and is owned by The Walpole Foundation, the nonprofit dedicated to preserving historic properties and open space for the long-term benefit of the town. Under the Foundation’s stewardship, Griswold Place continues to serve the community while retaining the architectural character that links it to Aaron P. Howland and the early development of Westminster Street as a cohesive civic streetscape.

14 Westminster Street — Tin Shop Lot

Known historically as the Tin Shop Lot, this narrow parcel reflects Walpole’s nineteenth-century village economy rooted in skilled trades and everyday commerce. Acquired by Aaron P. Howland in 1833 and defined by a distinctive lot line established in 1835, the site was long occupied by a tin shop serving essential household and industrial needs. Over time, successive tenants produced and repaired stoves, pipes, cookware, pumps, and other metal goods vital to daily life. Though modest in scale, the site preserves the story of the artisans and small businesses that sustained Walpole as a working village.

14 Westminster Street occupies what was historically known as the Tin Shop Lot. In 1833 George Huntington, proprietor of the nearby village tavern, sold this parcel to Aaron P. Howland. At that time the purchase included the land that later became the Village Tavern lot at 10 Westminster Street. Two years later, in 1835, Howland sold the west 19 feet of the lot to Susan Jones, establishing the narrow lot line that survives to this day.

Through the nineteenth-century the site was occupied by a tin shop, a utilitarian but essential village business. These shops fabricated and repaired household goods, stove and pipework, gutters, lanterns, and cookware, all services vital to both domestic life and local industry. The building was frequently leased, changing hands among a succession of tenants rather than long-term owner-operators.

By the 1870s, the business operating here had expanded its offerings considerably: advertisements list ranges, furnaces, stoves, pumps, lead pipe, kitchen furnishings, and tin, copper, and sheet-iron ware, reflecting the era’s growing domestic technology and the central role of metalworking trades in village life.

The tin shop site at 14 Westminster Street preserves an important strand of Walpole’s economic history, reminding us of the network of skilled artisans and merchants who supplied the everyday needs of the community.

10 Westminster Street — Village Tavern

This prominent parcel was part of the historic Village Tavern property and has long been a hub of changing commercial life in Walpole. During the nineteenth century it housed a boot and shoe shop, meat market, furniture store, oyster saloon, drug store, and even a dancing hall, reflecting the evolving needs and tastes of the village. Fires, changing ownership, and shifting enterprises continually reshaped the building while preserving its role as a center of activity. Under the stewardship of The Walpole Foundation, the site continues its mixed-use tradition with a restaurant at street level and apartments above, anchoring the vitality of Westminster Street.

The property at 10 Westminster Street occupies part of what was once the Village Tavern lot, a lively commercial block that evolved continually as Walpole’s needs changed. In 1842, Aaron P. Howland sold the property to merchants William C. Sherman (1807–1884) and Amherst K. Maynard (1821–1884). Only a few years later, in 1851, Sherman sold his interest to Maynard, who transformed the building into a boot and shoe establishment. Maynard’s shop was typical of mid-nineteenth-century village manufacturing: the salesroom was on the ground floor, while the stock was produced upstairs, making the building both a workshop and a storefront. Maynard’s declining health forced him to liquidate his business in 1873.

A fire in 1877 marked a turning point in the building’s commercial life. After the fire, George F. Chandler and Fred A. Lebourveau (1854-1934) opened a meat market, reflecting the rise of specialized food shops in small towns during this period. By 1879, the building had shifted uses again, becoming a furniture store, with an oyster saloon in the basement.

Under John C. Howard, who purchased the property after 1885, the building continued to diversify. A dancing hall operated on the upper floor, while the ground floor hosted a drug store between 1894 and 1898. Through the early twentieth-century the storefronts continued to change: during the 1920s, the building housed a jewelry shop, followed later by the Peck Drug Store, remembered by many longtime residents.

In the modern era, the property was acquired by The Walpole Foundation, ensuring its continued use in support of the village center. In honor of the benefactor who helped finance the restoration, the building bears a plaque identifying it as the “Leslie S. Hubbard Block.” The ground floor is now home to Rancho Viejo, a Mexican restaurant, while the upper stories provide rental apartments, continuing the building’s long tradition of flexible, mixed-use commercial life.

8 Westminster Street — Old Fire House

Built in the early 1950s on the site of a former livery stable, this modest mid-century building reflects Walpole’s transition from horse-powered services to modern municipal infrastructure. It served for decades as the town’s fire station during a period of civic modernization. As emergency services outgrew the site, the building was retired from public use and later acquired by The Walpole Foundation. Adaptively reused as commercial space, the former firehouse marks the evolution of Westminster Street from nineteenth-century service corridor to a mixed residential, commercial, and civic streetscape.

The building at 8 Westminster Street stands on a parcel sold in 1952 by Mrs. Emma Graves (1863-1961) specifically for the construction of a new Walpole fire station. At the time, the site was occupied by an old livery stable, a reminder of the era when horses and wagons were essential to village life and when Westminster Street served as an active service corridor just off Main Street. Mrs. Graves late husband, Russell George Graves (1862-1943) had owned the livery stable and reportedly kept 32 horses there. Having the new firehouse set back from the road was a practical choice, allowing trucks to maneuver easily and reducing noise and visual impact on the street.

The resulting mid-century building served the town’s fire department for decades, representing an important moment in Walpole’s civic modernization. As equipment grew larger and emergency services became more centralized, the fire department eventually relocated to more suitable quarters elsewhere in town.

Following its decommissioning, the building was acquired by The Walpole Foundation. The former firehouse was converted into commercial space, and it is now home to financial advisor Edward Jones, while the structure retains the clean, utilitarian lines typical of small, mid-twentieth-century municipal buildings.

The site marks the transition between Westminster Street’s nineteenth-century residential and commercial buildings and the civic improvements of the twentieth-century, an illustration of how the village has continued to evolve while maintaining its historic character.

11 Westminster Street — Site of The Walpole Inn

Originally developed around 1841 as a substantial private residence for William Mitchell, this prominent site later became one of Walpole’s most important landmarks. In 1902, Copley Amory transformed the house into The Walpole Inn, expanding it into a popular destination while also advancing modern village infrastructure through new water and sewer systems. For decades, the Inn served travelers, summer residents and social life in Walpole before falling into decline. Although the building was demolished in 1962, the site continues to serve the community as the home of the Savings Bank of Walpole and the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Clinic, carrying forward its long civic role.

The parcel at 11 Westminster Street was originally developed around 1841 when James L. Mitchell (1817-1880), a prosperous hotelier based in New York City, built a large house here for his father, William Mitchell (1788-1881). Mitchell was the owner of the “Hotel Brunswick” in New York City and had the means to build a substantial and comfortable dwelling in Walpole for his father’s retirement.

Although built by someone experienced in hospitality, the house initially served as a single-family residence, reflecting both its scale and its rural setting just off the village’s Main Street. Over the ensuing decades, the property passed through several private owners, each contributing to the architecture and character of the building.

In 1902, the property was purchased by Copley Amory (1866-1960), a scion of a prominent Boston family. Copley Amory came from a well-documented mercantile and socially prominent New England lineage: the extended Amory, Sullivan, Coffin, and related families of Boston long maintained business, estate, and social ties, with records going back to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Under Amory’s ownership, the house was completely remodeled and converted into The Walpole Inn. Porches were added, new wings constructed (including an east wing and a rear wing), and a stable was removed to make way for modern accommodations. Early in its life as an inn, the property was quite active: the main house served as the core lodging, while a nearby building was acquired as an annex to house overflow guests; its barn became a garage as automobile travel became more common.

But Amory’s influence on Walpole extended beyond hospitality. As he developed the Inn, he also launched major civic infrastructure projects: in 1903 he was one of seven Walpole men granted a charter to create the Walpole Water & Sewer Company to supply pure water to the village for domestic use, manufacturing and fire protection. He laid sewer lines along Westminster Street and down to the river, laying the groundwork for modern municipal services.

The transformation of the Mitchell house into The Walpole Inn under Copley Amory reflects more than a change of use; it marks a phase of modernization, linking the village’s nineteenth-century architecture and commerce to the evolving demands of the early twentieth-century.

The Inn operated for decades, drawing visitors, summer residents, and travelers. According to local histories, in its peak years the lawn was used for dancing, and the annex accommodated guests at high demand. The property at one time even featured a swimming pool below grade and lawns used for bowling.

By the mid-twentieth-century the building had fallen into disrepair. In 1962, the house was razed when the property was taken over by the Savings Bank of Walpole, which built a new facility on the site. Later, the site was acquired by The Walpole Foundation, ensuring that the property would remain under local stewardship and serve community needs. The Savings Bank of Walpole maintains a branch here, and a majority of the office space is now home to the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Clinic, which has been providing medical services to the community since 1982.

While the original inn no longer stands, its memory and the significant contributions of both the Mitchell and Amory families to Walpole’s built and civic environment remain central to understanding the village’s evolution.

51 Main Street — Jake’s Market & Deli — Site of Craft’s Tavern / Hotel Wentworth / The Dinsmore / Red Mill Inn

This busy corner has been a center of travel and commerce in Walpole since the early nineteenth century. First established as Craft’s Tavern before 1793, and later known as The Hotel Wentworth, it served as a major stagecoach stop on routes linking Boston, the Connecticut River Valley, and northern New England. Closely associated with stage operator Otis Bardwell, the tavern provided lodging, meals, and stabling at a time when Walpole was a vital transportation crossroads. Although the original building is gone, today’s market and filling station continue the site’s long tradition of serving travelers and the village alike.

The busy commercial corner at 51 Main Street, now home to Jake’s Market & Deli and the adjacent Irving Oil filling station, has been a hub of travel and activity in Walpole for nearly two centuries.

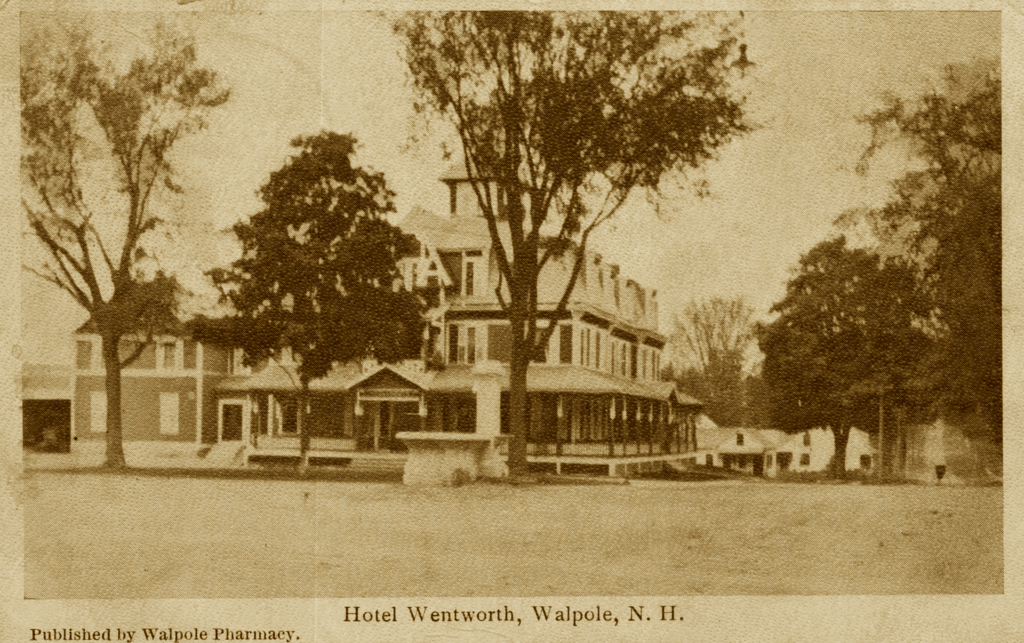

An inn stood on this site by the late eighteenth century, first known as Craft’s Tavern, which was in operation by 1793. During the early nineteenth century, as stagecoach traffic increased through the Connecticut River Valley, the tavern became one of Walpole’s most important public houses. In 1838, the property was leased by George Huntington to Justus W. Brown, and during this period it became known as the Hotel Wentworth, one of the most prominent stage stops in the region.

Walpole was a key crossroads on stage routes linking Boston with Burlington, Vermont, and Hanover, New Hampshire, while also connecting smaller river-valley towns to these main lines. Passengers, mail, freight, and news all passed regularly through the village, bringing steady business to its inns and taverns.

A central figure in this network was Otis Bardwell (1792–1871), a Walpole entrepreneur and stage driver who operated several stage and mail lines through the village. Under his direction, establishments such as Craft’s Tavern and the Hotel Wentworth prospered, providing travelers with meals, lodging, and stabling for horses. These inns also served as important social centers, hosting meetings, celebrations, and informal gatherings.

In the early twentieth century, the hotel was renamed The Dinsmore, and by the 1920s it was known as the Red Mill Inn. As automobile travel replaced stagecoaches and railroads reshaped regional transportation, the old hotel declined. By 1950, the building was demolished and replaced by a Gulf Oil service station. The concrete-block structure built at that time to house automobile service bays survives today, repurposed as Jake’s Market & Deli.

Though the original tavern and hotel no longer stand, this corner continues its long tradition of service to travelers, echoing its historic role as one of Walpole’s principal centers of hospitality, commerce, and movement.

Turn around and walk West past 20 Westminster Street

22 Westminster Street

Originally built around 1790 in neighboring Westmoreland, this house was carefully dismantled and relocated to Walpole about 1940 by P. Lucile Tucker (Hawley) Bragg. Reassembled on Westminster Street, the timber-frame structure retains the proportions and character of a late eighteenth-century New England dwelling. Local lore surrounding its placement, reportedly positioned deliberately close to the neighboring Aaron P. Howland House, adds a human dimension to its history. The house contributes an earlier architectural layer to the streetscape, linking Westminster Street to the region’s colonial building traditions and personal village stories.

22 Westminster Street has a unique story: it was originally built circa 1790 in Westmoreland, New Hampshire, and was disassembled and relocated to Walpole around 1940 by P. Lucile Tucker (Hawley) Bragg (1884-1953), then the owner of 24 Westminster Street next door. She had purchased it from Robert Moore of Westmoreland. The move was a significant undertaking, carefully transporting the timber-frame structure and reconstructing it on its new lot.

According to local lore, Mrs. Bragg was not particularly fond of Guy H. Bemis, then the owner of 20 Westminster Street (the Aaron P. Howland House). She positioned the relocated house as close as possible to Mr. Bemis’ property, much to his dismay. Reportedly he was incensed about it. Relations between the parties must have thawed, because years later Marion Bemis is identified as the “Informant” on Mrs. Bragg’s death certificate.

The house itself retains the character of its late-eighteenth-century origins, with timber-frame construction and traditional proportions typical of New England homes of the period. Its presence on Westminster Street adds a layer of historical intrigue to the block, illustrating both the region’s architectural heritage and the personal stories that shape the village’s social landscape.

24 Westminster Street — Susan Bellows Robeson House

Built around 1821 for Susan Bellows Robeson, granddaughter Col. Benjamin Bellows, Walpole’s founder, this refined house is considered the town’s earliest example of Greek Revival architecture. Modest in scale yet elegant in proportion, it reflects both changing architectural tastes and the aspirations of Walpole’s early nineteenth-century families. The home is closely associated with Susan Robeson’s strength of character and civic spirit, remembered in local tradition at the time of her death. Later owned by antiques dealer and preservation-minded P. Lucile Tucker (Hawley) Bragg, the house continues to embody the layered personal and architectural history of Westminster Street.

Built circa 1821 for Susan Bellows Robeson, daughter of Colonel Joseph Bellows (1744-1817) and granddaughter of Colonel Benjamin Bellows (1712-1777), Walpole’s founder, this refined house is widely regarded as the town’s earliest example of Greek Revival architecture. Modest in scale yet formal in expression, it marks a clear departure from the earlier Colonial houses nearby and reflects Walpole’s early embrace of national architectural trends.

The house is distinguished by its temple-like front façade, dominated by a full-height portico with tall classical columns supporting a triangular pediment. The smooth, white exterior finish, strong cornice line, and symmetrical window placement emphasize order, proportion, and restraint, all hallmarks of the Greek Revival style. Unlike later, more elaborate examples, this early version is intentionally restrained, translating monumental classical forms into a dignified village residence suited to a small household.

Designed and built by Levi Hubbard (1764–1831), the house was intended for Susan Bellows Robeson (1780–1860), eldest daughter of Colonel Joseph Bellows (1744-1817) and granddaughter of Colonel Benjamin Bellows (1712-1777), Walpole’s founder. Recently widowed at the time of construction, Susan Robeson managed the household while raising two children alongside four stepchildren from her husband Major Jonas Robeson’s earlier marriage, embodying both independence and civic responsibility.

Local tradition preserves a vivid story of her character. On the night of her death, as Walpole prepared a torchlight procession in support of Abraham Lincoln’s election, every house around the Common was to be illuminated. When told her windows were dark so she might rest more comfortably, Susan replied:

“Let every pane of glass in every window of this house be lighted at once if there are candles enough in town to do it.”

She died before morning.

In the twentieth century, the house entered a new chapter when it was purchased in 1932 by P. Lucile Tucker (Hawley) Bragg (1879–1953), a schoolteacher and antiques dealer who sold and displayed items from the barn on the property.

The Susan Bellows Robeson House stands as a landmark of architectural transition on Westminster Street, linking Walpole’s founding families, early Greek Revival design, and generations of residents whose lives shaped the village’s civic and cultural identity.

Excursus: Colonel Benjamin Bellows (1712-1777), Founder of Walpole

Col. Benjamin Bellows (1712–1777) was the central figure in the founding of Walpole, New Hampshire. A surveyor by trade, he secured the original grant for “Number 3” in 1736, organized the first proprietors, and led early settlers in establishing the community, serving as militia colonel, magistrate, and principal landholder. His homestead, while outside the village center, remained prominent through successive owners, including Copley Amory, who preserved and enhanced the property in the early twentieth century. Later the house became The Stagecoach Inn and is now The Bellows Walpole Inn. Bellows’ leadership and vision laid the foundations for Walpole’s enduring civic and social life.

Col. Benjamin Bellows was the central figure in the founding and early development of Walpole, New Hampshire. Born in Lancaster, Massachusetts, in 1712, he began his career as a surveyor and became well known on the colonial frontier for his skill in land assessment and his relations with Indigenous communities. His surveying work for the colonial government brought him into the upper Connecticut River Valley, where he recognized the agricultural promise of the region’s fertile intervale lands.

In 1736, Bellows received the original grant for what was then known as “Number 3,” the third in a chain of strategically placed settlements intended to secure the Massachusetts frontier. He organized the first proprietors, oversaw early surveys and lot divisions, and led the initial group of settlers who established the community. As Walpole grew, Bellows emerged as its most influential figure: serving as militia colonel, magistrate and principal landholder. His leadership during periods of frontier conflict, when fortified houses and coordinated defense were essential, helped ensure the settlement’s survival.

Since Bellows’ original homestead stands on the outskirts of town, it lies too far from the village center to be included in this walking tour.

The property remained significant long after his death in 1777. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries it entered a new phase when it became the residence of Copley Amory (1890-1964) of Boston, who owned the estate for thirty-five years (he also owned The Walpole Inn on Westminster Street). A member of a prominent Boston family, Amory invested heavily in the preservation, improvement, and adornment of the historic homestead, ensuring that the house and grounds retained their stature as one of Walpole’s most distinguished properties. His stewardship represents an early example of the interest urban elites took in the preservation and enhancement of New England’s historic rural properties.

Following the Amory era, the house evolved with changing community needs. It was operated for a time as The Stagecoach Inn, providing lodging and hospitality, and later served as a nursing home, a role that reflected mid-century adaptations of large historic houses for institutional use. Currently the property operates as The Bellows Walpole Inn, offering lodging, dining and an event venue. Its modern function continues a centuries-long tradition of the homestead serving as a prominent and welcoming presence in the life of the town.

By the time of his death, Bellows had laid the essential foundations for the enduring New England community we explore today. His descendants would continue to shape local and national history, but Col. Benjamin Bellows remains the energetic founder whose efforts transformed a remote frontier tract into a thriving village.

Turn Right (North) on Elm Street

15 Elm Street — Stephen Rice House

15 Elm Street is a modest, well-preserved early–nineteenth-century Cape, distinguished by its low profile, central chimney, symmetrical façade, and simple doorway—features typical of Walpole’s post-Federal rural domestic architecture and suggesting practical craftsmanship rather than display.

This kind of early-nineteenth-century Cape is one of Walpole’s most enduring house forms. Compact, efficient, and well-proportioned, such houses were built to meet everyday needs rather than to announce status. Constructed of white painted clapboard, their simplicity reflects a building tradition grounded in function, local materials and continuity rather than fashion.

Stephen Rice acquired the lot in 1818, lost and regained it amid financial trouble, and died insolvent by 1846, leaving a tangled estate settled by others. Over the next century the house passed through a succession of owners whose occupations—master carpenter, merchant-tailor, farmer, cabinetmaker, undertaker—trace the changing and often precarious working lives that sustained Walpole.

15 Elm Street stands not just as a representative house form, but as a reminder that modest buildings often witnessed complex personal histories marked by effort, adaptation, and uncertainty behind their calm and orderly exteriors.

14 Elm Street — Howland–Schofield House

Built in 1844 by master builder Aaron P. Howland for his own family, this distinctive residence showcases an unusual blend of Greek Revival and Gothic Revival design. Classical elements, including a double front portico with Corinthian columns inspired by Asher Benjamin, are paired with pointed-arch pediments that give the house a picturesque Gothic character. The craftsmanship reflects Howland’s experimentation and confidence at the height of his career. The house continues its legacy of creativity as the home of Florentine Films, linking Walpole’s architectural heritage to nationally significant storytelling.

Dating from 1844, the Howland–Schofield House is one of Walpole’s most architecturally distinctive residences, reflecting the creative range of local builder Aaron P. Howland. This 1½-story home blends elements of both the Greek Revival and the Gothic Revival, two styles that were coming into vogue in New England during the mid-nineteenth-century. The result is an eclectic design that demonstrates Howland’s willingness to combine tradition with emerging tastes.

The house’s double front portico, supported by ornate Corinthian columns, showcases the classical influence. These columns closely follow the plates published by architectural pattern-book author Asher Benjamin, whose guidebooks were widely used by New England builders seeking to reproduce fashionable Greek Revival details. In contrast to these classical features, the house also incorporates unmistakable Gothic Revival motifs. Most striking are the pointed-arch Gothic pediments repeated above the portico and echoed across the numerous windows and dormers. This rhythmic use of pointed arches gives the house a picturesque, vertical emphasis, softening the classical symmetry with a touch of romantic flair.

The main entrance door bears a strong resemblance to the doorway at 20 Westminster Street, the Aaron P. Howland House, suggesting that Howland favored the design enough to adapt it here. Aaron P. Howland and his family lived in the Elm Street house for many years before his widow sold the property in 1884 to George P. Porter (1834-1923). A later owner, Norman Schofield (1908-2002), lends his name to the house’s modern designation among the records of the Library of Congress, Historic American Buildings Survey. Schofield had purchased the property from P. Lucile Tucker (Hawley) Bragg, who noted:

“It was the superior and unusual construction of the house with its attractive Gothic windows and detail that tempted me to see just what I could make of it. The fact that the house was built by Aaron P. Howland for his own family undoubtedly accounted for its superior construction. The cellar walls are unusually thick and the cellar itself is divided into three separate rooms. The outside walls of the house are of brick covered over with wood, while the chimney at the back of the house has built into it on the second floor a complete outfit for smoking meat.”

This historic residence has taken on a new and notable role: it serves as the offices and production studio of Florentine Films, the documentary film company led by Ken Burns, whose work has brought national attention to American history and culture. The building’s preservation and active use add a contemporary chapter to its long and varied story.

The distinctive Gothic pointed-arch pediments featured here provide a valuable clue to Howland’s broader body of work. Two similar houses in Bellows Falls, Vermont, at 9 School Street and 107 Atkinson Street, display identical pointed arch pediment designs over the windows, strongly suggesting that they too were constructed by Aaron P. Howland. Together, these buildings help define a recognizable stylistic signature for one of the Connecticut River Valley’s most skilled nineteenth-century builders.

Return to Westminster Street

36 Westminster Street — St. John’s Episcopal Church

St. John’s Episcopal Church, built in 1902–1903, occupies a site long central to Walpole’s community life. Originally home to a village schoolhouse, the church was built through the generosity of Hudson E. Bridge, who donated the land in memory of his young daughter Katherine. Designed by the prominent St. Louis firm Mauran, Russell & Garden, the building blends Arts and Crafts and Gothic Revival influences in a carefully crafted structure. Consecrated in 1903, St. John’s serves as both a memorial and an enduring architectural landmark, reflecting the impact of summer residents and local philanthropy on Walpole’s civic and spiritual landscape.

This site has been a center of community life in Walpole for more than two centuries. The first building here was a village schoolhouse erected in 1807. Designed with three classrooms and an expansive second-floor exhibition hall, it served younger students from the village until 1854, when the new elementary school opened on School Street behind The Walpole Academy. After its educational use ended, the building found a second life as R. L. Ball’s shoemaker’s shop, a reminder of the small trades that once supported daily life in Walpole. The old schoolhouse was eventually demolished to make way for the present church.

The land for St. John’s Episcopal Church was a gift from Hudson E. Bridge (1858-1934), presented to the parish on August 1, 1902, as a memorial to his young daughter Katherine Bridge (1897–1900). Katherine died at the age of three, and her photograph is still displayed inside the church on the west end of the south wall; it remains a poignant reminder of the personal loss that shaped the church’s origins.

Hudson E. Bridge was a member of a prominent midwestern industrial family. The Bridges were influential in St. Louis, where they helped establish one of the nation’s largest hardware firms, H. E. & A. F. Bridge Company, descended from the well-known Bridge & Beach Manufacturing Company. Although the family’s primary business interests were centered in Missouri, they maintained connections to New England, and Hudson Bridge spent extended periods in Walpole. His gift of land reflects the pattern of affluent summer residents shaping Walpole’s civic landscape in the early twentieth-century.

The church building was designed by the distinguished St. Louis architectural firm Mauran, Russell & Garden, which was uniquely qualified to execute this building. John Lawrence Mauran was a nationally recognized architect, Ernest Russell contributed significantly to the firm’s ecclesiastical work, and William DeForest Garden had New England roots that may have helped connect the firm to the Walpole commission.

The partnership was known for adapting Arts and Crafts and Gothic Revival influences into refined, well-crafted buildings, qualities that are evident in St. John’s Church.

Groundbreaking took place in 1902, and construction moved swiftly. The first service was celebrated in 1903, followed by the laying of the cornerstone. The formal consecration occurred on September 5, 1903, led by The Rt. Rev. William Woodbury Niles, D.D., Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New Hampshire. Bishop Niles (1832–1914) was a respected scholar and church leader, serving as bishop from 1870 until his death. He oversaw a period of significant growth in the diocese, supporting the establishment of churches in both rural and urban communities.

St. John’s stands as both an architectural landmark and a memorial woven into the personal history of one family and the broader story of Walpole’s development at the turn of the twentieth-century.

Turn Right (West) on Westminster Street

40 Westminster Street — Holland House

Built around 1833 on land owned by John Bellows, this house originally reflected the transitional Federal-to-Greek Revival style typical of the period. Over the decades, it was altered with a third floor addition and other updates, transforming it into a larger, more flexible residence. In 1907, Mary Holland established it as The Holland House, a small lodging that welcomed visitors to Walpole’s summer community. Converted into apartments, the building preserves layers of architectural and social history, from its early nineteenth-century origins to its role in early twentieth-century village hospitality.

Built around 1833, this house stood on land owned at the time by John Bellows (1768–1840), who also owned the adjoining property at 48 Westminster Street (see that entry below for more on Bellows). While the architect or builder is not known, the house’s original form likely reflected the transitional Federal-to–Greek Revival idiom common in Walpole during the 1830s, characterized by straightforward massing and restrained detailing.

Bellows’ widow, Anna Hurd Langdon Bellows (1781–1860), sold the property in 1854, and in the decades that followed the house was significantly altered by later owners. The most dramatic change was the addition of a full third floor, which reshaped the original roofline and expanded the interior living space. Other updates over the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries further evolved the structure from a modest early residence into a more flexible, multi-use house.

In 1907, a subsequent owner, Mary Holland (1858–1937), established the property as The Holland House, a small lodging house that quickly became a favored stopping place for visitors arriving to open or preparing to close their summer homes in and around Walpole. Its position on Westminster Street, close to the village center yet slightly removed from Main Street, made it an inviting and convenient waypoint.

Following its period as a guest house, the building continued to adapt to changing needs and has since been converted into apartments. Even so, the house retains elements of its layered history: an 1830s core, substantial nineteenth- and twentieth-century alterations, and its brief but memorable early-twentieth-century life as one of Walpole’s modest seasonal lodgings.

43 Westminster Street — Stephen Rowe Bradley House

Built around 1808 for lawyer and legislator Francis Gardner, this Federal-style house later became the home of Vermont statesman Stephen Rowe Bradley. Instrumental in Vermont’s entry into the Union, Bradley lived here from 1817 to 1830, making the house a hub of family, legal, and political activity. Its 2½-story frame, hip roof, and well-proportioned Federal details reflect the elegance and symmetry of the style favored during the early republic. The property’s later use by the New Hampshire Asylum for the Insane and its return to private ownership underscores its enduring prominence in Walpole.

43 Westminster Street is on the National Register of Historic Places, and is a distinguished example of Federal-style architecture in Walpole. The house was built circa 1808 for Francis Gardner (1771-1835), a lawyer and state legislator, and later became the home of Stephen Rowe Bradley (1765–1830), a Vermont lawyer, judge and politician.

Bradley played a key role in Vermont’s entry into the United States as the fourteenth state in 1791, representing the independent Vermont Republic in negotiations over its boundaries. He resided at this house from 1817 to 1830, during which time it served as both a family home and a center of legal and political activity.

The large 2½-story frame house features a hip roof, two interior brick chimneys, and a white clapboard exterior. Its well-proportioned Federal-style details reflect the architectural ideals of the early republic, emphasizing symmetry, restraint, and elegance. The house remained prominent in Walpole’s civic life through the nineteenth-century: in the late 1800s, it was owned by the New Hampshire Asylum for the Insane, before returning to private hands in 1913 when acquired by Henry K. Willard of the extended Bradley family.

The Stephen Rowe Bradley House remains a striking example of early nineteenth-century architecture and a tangible link to both Vermont and New Hampshire history, commemorating the life of a man central to the formation of the United States’ northeastern boundaries.

48 Westminster Street — John Bellows House

Built in 1833 by John Bellows upon his return to Walpole after a successful business career in Boston, this house overlooks the Connecticut River and showcases a striking Greek Revival temple-front portico that wraps three sides. Its long ell connecting to the barn blends Federal-era refinement with emerging Greek Revival details, reflecting the architectural transition of the 1830s. Bellows, a prominent businessman and civic leader, was remembered by his son as a man of intellect, integrity,and public spirit. The house stands as both an elegant example of its era and a testament to the Bellows family’s influence on Walpole.

According to The Bellows Genealogy, or John Bellows, the Boy Emigrant of 1635 and His Descendants, by Thomas Bellows Peck, John Bellows (1768-1840), son of Joseph Bellows and a grandson of Col. Benjamin Bellows, had removed from Walpole to Boston, becoming head of the firm of Bellows, Cordis & Jones, an importer of English dry goods, who managed to retire at the age of fifty with an ample fortune. He was president of Manufacturers’ and Mechanics’ Bank of Boston, and served a number of years as an alderman. He resided in Boston on Tremont Street.

His fortunes turned during a fiscal crisis in 1830, and in June 1833 he returned to Walpole and built this house on the brow of the hill overlooking the Connecticut River. The house features a Greek portico that wraps around three sides, giving the structure a strong temple-front presence characteristic of the period. The long ell connecting the house to the barn retains a blend of Federal-era refinement and emerging Greek Revival detailing, illustrating the architectural transition underway in Walpole during the 1830s.

An address by John Bellow’s son, Rev. John Nelson Bellows (1805-1857) gave this description of him:

“He was a man of superior intellect, generous sentiments, and spotless integrity. Lavish in the education of his children, stern in his family government, proud and modest, tender at heart but ashamed of his sensibility, full of public spirit, unsurpassed in sharpness of wit and readiness of repartee — dignified and scrupulous in his costume and manners elegant in the neatness of his style and his handwriting, admirable as a letter writer, and excellent talker, fond of speculation and argument, a keen man of business — a philosopher in his sorrows and disappointments though easily annoyed by trifles, John Bellows (whom a thorough education would have made a very remarkable man) deserves this tribute of affectionate respect from his children, and the grateful remembrance of his fellow citizens of Boston.”

Return to Elm Street; turn Right (South)

34 Elm Street — Town Hall

Walpole’s Town Hall has been the village’s center of civic life for over two centuries. The original Prospect Hill Meetinghouse (1792) building was moved to the village common in the 1820s and served as a combined town and church space until 1844. After the old structure was destroyed by lightning in 1917, the current building was designed by Boston architect James Purdon. The Town Hall continues to host town offices, meetings, and community gatherings, linking modern Walpole to its longstanding tradition of local governance.

Walpole’s Town Hall, located at 34 Elm Street, has long been the center of civic life in the village. Its story begins with the Prospect Hill Meetinghouse, completed in 1792. In the 1820s, this building was dismantled and moved to the village common, where it continued to serve as both a place for town meetings and church services until 1844, when control officially passed to the town.

The original building endured for decades, witnessing the growth and evolution of the community. Tragically, in 1917, the old Town Hall was struck by lightning and destroyed by fire. The replacement building you see today was designed by James Purdon of Boston, reflecting early twentieth-century architectural sensibilities while maintaining the Town Hall’s central role in civic life.

The Town Hall continues to house town offices, meetings, and public and private gatherings, linking the modern village to its long history of self-governance and community involvement. The site embodies both Walpole’s early colonial civic traditions and its adaptation to the architectural and functional needs of the twentieth-century.

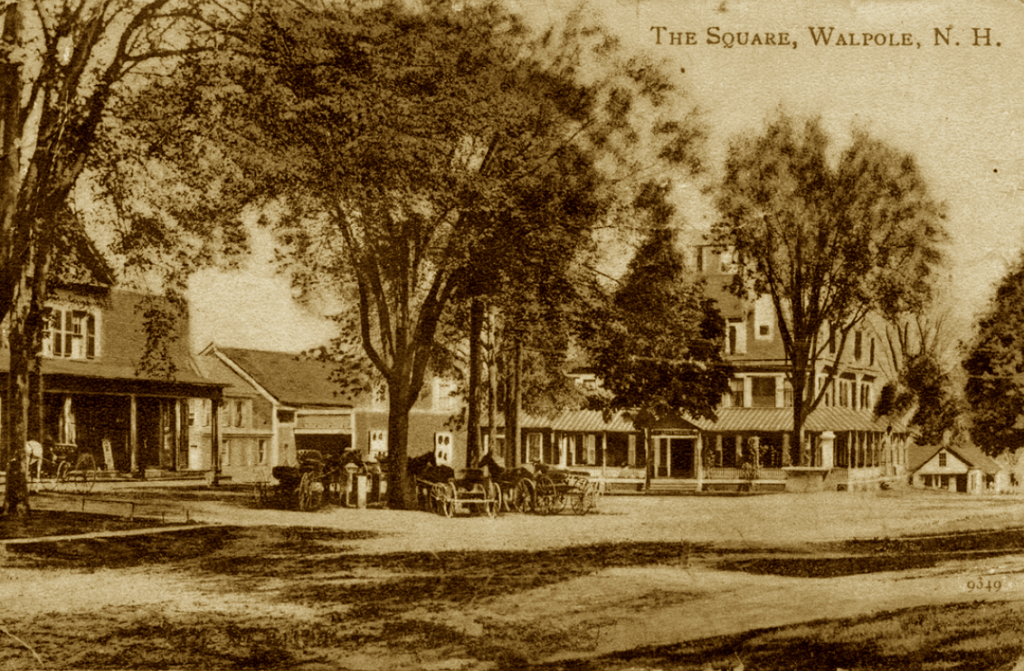

Town Common — Washington Square

Washington Square, Walpole’s Town Common, has served as the village’s physical and symbolic center since the eighteenth century. Originally a shared open space for military drills, meetings, and everyday social interaction, it later hosted recreational activities like tennis and baseball while remaining carefully regulated to preserve its character. In the twentieth century, the Common gained new commemorative features, including the War Memorial and the village Christmas tree, connecting past and present. Surrounded by historic buildings, it continues to be a gathering place for seasonal events, civic functions, and daily life, embodying the town’s enduring commitment to community and shared space.

The Town Common (formally Washington Square) has been the physical and symbolic center of Walpole since the eighteenth-century. Laid out as a shared open space, it served many of the functions essential to early New England town life: a place for military drills, public meetings, recreation, celebration, and the everyday mixing of neighbors. Its broad, grassy expanse has long embodied the community’s traditions of civic participation and common use.

By the late nineteenth-century, the Common had become a lively focus of organized recreation. Tennis courts appeared in 1883, and baseball games drew enthusiastic crowds—occasionally too enthusiastic, as suggested by an 1884 complaint about the players’ “noisy and profane” language. In response to increasing activity, the town established regulations to protect the space, prohibiting cannon fire and circus exhibitions on the Common. (the street sign in the lower right corner of the photograph above reads “Keep Horses Off Common”). These rules reveal both its popularity and the community’s desire to balance enjoyment with preservation.

The twentieth-century added new layers of meaning. A fund for a village Christmas tree began in 1920, and in 1935 a spruce was planted at the north end of the Common that is still illuminated each winter. Just a few years earlier, in 1921, construction had begun on the War Memorial, honoring the men of Walpole, North Walpole, and Drewsville who served in World War I. The monument was later updated to include veterans of all subsequent conflicts, and flanked by two 75mm Krupp mountain cannon, it remains a solemn anchor at the edge of this shared green.

The Town Common continues to serve its historic purpose: a gathering place at the center of village life, ringed by some of Walpole’s most distinguished buildings and alive with seasonal events, quiet conversations and everyday passersby. Its long, evolving history reflects the town’s commitment to shared space and the belief that a community is strengthened by the places where people naturally come together.

38 Elm Street — River Valley Church

Built in 1845, this building has served multiple congregations, including Methodist, Episcopalian, Catholic and Evangelical communities, reflecting the evolving religious life of Walpole. Its simple, mid-nineteenth-century design exemplifies New England village church architecture while accommodating functional needs over time. After St. Joseph’s Catholic Church relocated in 2011, the building was revitalized as River Valley Church in 2024, continuing its long tradition as a place of worship. The structure preserves its historic character while supporting the spiritual and social life of the modern village.

In 1844 this lot was sold off from the meeting house lot, which in turn in 1848 was sold to a group representing the Methodist Church. The building dates from 1845. In 1868, James L. Mitchell purchased it for the Episcopalian Church, which then sold it to the Catholic Church five or six years later. These changes in ownership and denominations reflect the changing demographics and religious life in Walpole.

After St. Joseph’s Catholic Church relocated to North Walpole (joining the congregation of St. Peter’s Catholic Church) in 2011, the building found new life as River Valley Church, an Evangelical congregation that began services there in 2024, continuing its long-standing role as a place of worship and community gathering. The structure retains its historic character, reflecting mid-nineteenth-century church architecture with a simple, functional design typical of New England village houses of worship, while also adapting to the needs of its modern congregation.

River Valley Church continues to serve as a spiritual and community center, illustrating the evolving religious landscape of Walpole while preserving an important historic structure on Elm Street.

44 Elm Street

44 Elm Street is a representative village house, illustrating the solid, restrained dwellings that formed the everyday fabric of Walpole in the years following the Revolution. Standing on land once owned by Samuel and Phebe Bellows Grant, it reflects the gradual subdivision of large house lots around Washington Square and the close relationship between prominent families and village growth.

The land on which this house stands was originally part of the Grants’ extensive holdings associated with the Bellows–Grant House at 42 Main Street. In 1806 they sold this portion of their property (eight rods south on the west side of what was then Washington Square), beginning a long sequence of transactions that helped transform large house lots into the dense, walkable village center we recognize today.

By 1810 the property was occupied by Oren Hall, who lived here while operating a shop just to the south. This detail highlights an essential feature of early Walpole: it was a working village, not rigidly divided into residential and commercial zones. Houses, shops, and small enterprises stood side by side, especially around Washington Square, allowing daily life to unfold within a compact area.

Over the next several decades, the house passed through the hands of clothiers, merchants, clergy, and families whose names recur throughout Walpole’s records: Chandler, Adams, Gage, Bellows, Sherman and Johonnot. The succession of owners illustrates continuity rather than change. The house was repeatedly adapted, maintained, and inhabited, rather than replaced. Its significance lies not in prominence or display, but in how it helps explain the lived-in, layered character of Walpole village itself.

Look at the buildings across the Common on Washington Street

9 Washington Street

Built in 1839, this house is a well-preserved example of Walpole’s late Federal–early Greek Revival architecture, with its steep front-facing gable, symmetrical façade, and classical porch reflecting the town’s taste for dignified restraint. Likely built for John Williams of Cambridgeport, it later became home to three women of the Williams family, highlighting a lesser-noticed but important pattern of women-centered households in nineteenth-century village life. Over time, the house passed through a series of regional owners, yet it has remained remarkably true to its original 1840s character.

Its steep, front-facing gable gives the building its distinctive triangular profile, a form that became popular in the 1830s as Greek Revival ideas were adapted to traditional New England houses. The white clapboard exterior, dark shutters, and overall restraint reflect Walpole’s long-standing preference for dignified simplicity rather than display.

The façade is carefully balanced, with symmetrically placed windows and a broad, full-width porch supported by slender classical columns. That porch introduces a clear Greek Revival note, while twin interior chimneys rising behind the ridge recall the house’s original heating and room arrangement. Set back on its lawn and framed by mature trees, the house retains the character of a prosperous nineteenth-century village residence.

The house’s ownership history is equally revealing. It was likely built for John Williams of Cambridgeport, Massachusetts, who purchased the land in 1839 and appears to have invested in a substantial, up-to-date home in Walpole. By the mid-nineteenth century, however, the house was occupied by three women: Eliza and Sophia Williams and Margaret Harrington. The fact that the house was occupied by three single women was not uncommon, but is often overlooked in village histories. Eliza later left the property to Margaret, who married Dr. George A. Blake in 1856.

Over time, the property passed through a succession of mostly absentee or non-local owners, including residents of Maine, New York and Rhode Island, reflecting Walpole’s gradual transition from a self-contained village to a town connected to wider regional networks. Despite these changes in ownership, the house has retained its essential 1840s character.

15 Washington Street — First Congregational Church

Established in 1832 by members who left the Unitarian “hill” society, the First Congregational Church was built on the Village Common as a new center for worship. In 1873, the building was raised 10 feet to add a vestry and kitchen beneath the sanctuary, enhancing its role in social and community life. The church remains an active congregation and a prominent architectural landmark, anchoring the eastern edge of the Common and reflecting nearly two centuries of religious and civic history in Walpole.

The First Congregational Church at 15 Washington Street was established when a group of Congregationalists withdrew from the “hill” society and formed their own congregation in late 1832. Over the following year and a half, the members built the church on the Town Common, establishing a new center for worship and community life.

In 1873, the building underwent a significant modification: it was raised 10 feet, and a vestry and kitchen were added beneath the sanctuary, expanding its functionality for social and community gatherings. This combination of architectural adaptation and continued use illustrates how the church has served not only as a place of worship but also as a hub for civic and social life in Walpole.

The First Congregational Church remains an active congregation and a prominent architectural and social landmark, anchoring the eastern edge of the Common and reflecting nearly two centuries of religious and community history in the village.

19 Washington Street — Congregational Church Parsonage

The Congregational Church parsonage is a prominent late-eighteenth-century village house, likely built in the 1790s by cabinet-maker Nicanor Townsley, and later refined with Greek Revival details. Its symmetrical façade, arched attic window, and classical porch reflect Walpole’s early prosperity and taste. Long associated with the Dana, Bellows, and Grant families, the house was a center of domestic and intellectual life before being given to the Congregational Church in 1883, securing its enduring role in the religious and architectural history of Walpole.

This house, now used as the Congregational Church parsonage, is a distinguished example of late Federal–early Greek Revival architecture, likely built in the 1790s. It is a large, symmetrical, two-and-a-half-story, wood-frame dwelling with a side-gabled roof, twin brick chimneys, and white clapboard siding—features typical of substantial New England village houses of the period.

One of its most notable architectural features is the arched attic window centered in the gable, a refined detail derived from Palladian design. The centered entrance, now sheltered by a Greek Revival porch with square columns, reflects later nineteenth-century improvements while maintaining the building’s formal balance. The evenly spaced multi-pane windows and dark shutters reinforce its orderly, classical character.

The house was likely built by Nicanor Townsley (1755-1830), a local cabinet-maker who acquired the property before 1795. Its careful proportions and fine details suggest the hand of a skilled craftsman. By the early nineteenth-century, it passed through several owners, including members of the Dana family.

In 1827 the property came to Submit Dana (1764-1836), the widow of Samuel B. Dana (d. 1825). Her daughter, Sarah Sumner Dana (1792-1867), lived here with her husband, Thomas Bellows II (1779-1825), and later raised her daughter, Sarah Isabella Bellows (1820-1866) in the house.

Sarah Isabella married George W. Grant (1812-1881), who came to Walpole in the 1840s after business reverses in Boston. Grant enlarged and improved the house and became known locally for his wit, humor, and literary talent. Evenings here were remembered as lively and stimulating, marked by conversation and playful verse.

After the deaths of members of the Grant family, the house declined until 1883, when it was given to the Congregational Church for use as a parsonage. Since then, it has remained a prominent and dignified presence in the village, reflecting both Walpole’s architectural traditions and its religious heritage.

Continue South on Elm Street

50 Elm Street — Former Mrs. Wright’s Boardinghouse / Elmwood Inn / Old Colony Inn

Built around 1811 by fur trader David Stone, this house blends Federal and Georgian architectural elements, including a fanlight, Palladian window, and two-story pilasters. In the mid-nineteenth century, it became a cultural hub, hosting performances by the Walpole Amateur Dramatic Company, including a notable 1855 production featuring Louisa May Alcott. Operating as the Elmwood Inn and later, the Old Colony Inn, it hosted James Michener while he researched his novel “Hawaii,” drawing inspiration from Walpole for his fiction. Now a private residence, the house preserves its architectural charm and its rich connections to Walpole’s artistic and literary heritage.

50 Elm Street was built circa 1811 by David Stone (1776-1839), a fur trader who had made his fortune in the early American fur business. The house showcases a blend of Federal and later Georgian architectural elements, including a fanlight over the front door, a Palladian window above, and two-story pilasters flanking the façade. Around 1868, a second-story porch was added, reflecting evolving tastes and use of the building.

The house is historically significant for its role as a cultural venue in mid-nineteenth-century Walpole. It was the site of performances by the Walpole Amateur Dramatic Company, which held productions in the attic. On 11 September 1855, both Louisa May Alcott and her sister Annie performed in The Jacobite and The Two Bonneycastles, entertaining 100 to 200 attendees. A review of this performance was later published in the Boston Gazette. At the time, the house was owned by Dr. Jesseniah Kittredge, who maintained the property from 1830 to 1868.

After Kittredge sold the property, it became Mrs. Wright’s Boarding House, which evolved into the Elmwood Inn. In 1930, Donald McNaughton of Lowell, Massachusetts purchased the inn and renamed it The Old Colony Inn. During the 1950s, while researching and writing his novel Hawaii (1959), James Michener resided here, using Walpole as the model for the hometown of one of the novel’s central families. In a 1969 letter to Walpole librarian Anita Aldrich, Michener described Walpole as “one of the most beautiful villages in the United States” and remembered that it was the view of the First Congregational Church parsonage across the Common from his window that inspired the residence of Michener’s Bromley clan.

The house is now a private residence, but it remains a notable site linking Walpole to Alcott family history, nineteenth-century village theater, and American literary culture, while also reflecting the architectural evolution of a prominent village inn over nearly two centuries.

Cross the Town Common (East) to the corner of Washington Street and Middle Street; Head East on Middle Street

As you cross the Common, you may notice the black granite bench centered on the porch of the Congregational Church parsonage. It is dedicated to Ronald Edward Frankiewicz (1946–2017), who was born in nearby Bellows Falls, Vermont, and spent his entire life in Cheshire County, residing in Walpole, Keene and neighboring Hillsdale, New Hampshire. In 2021, his widow, Marcia Frankiewicz, petitioned the village to place a memorial bench on the Common in his honor (at her expense). The Select Board chose this location, linking a personal remembrance to the shared landscape of the Common.

12 Middle Street

Built around 1793 by tanner David Stevens and moved to its current site circa 1839, this house features a Georgian-inspired façade with quoined corners, pilasters, and a central-hall plan. A later Colonial Revival porch blends historical styles, reflecting evolving architectural tastes. Beyond its design, the house played a significant social role in the mid-nineteenth century, sheltering runaway slaves as part of the local abolitionist network. It stands as a testament to both Walpole’s architectural heritage and the moral courage of its residents.

12 Middle Street was built circa 1793 by tanner David Stevens, and originally stood on Main Street, at the site now occupied by 27 Main Street. Around 1839, the house was moved to its current location on Middle Street.

Architecturally, the house exhibits a Georgian-inspired façade, sharing features with the nearby William Buffum House (25 Main Street), including quoining at the corners, molded window caps, pilasters flanking the entrance, a central-hall plan, and a five-light transom above the front door. The structure retains its original hipped roof, while a Colonial Revival porch was later added across the front, blending historical styles and reflecting evolving tastes.

Beyond its architectural significance, 12 Middle Street played an important role in social history. In the mid-1800s,

Capt. John Cole (1806-1875), born in Westmoreland, New Hampshire, lived here about 1847 to 1854. A genealogy of the Cole family by Frank T. Cole, The Early Genealogies of the Cole Families in America (1887) describes how:

“[In Walpole] he had extensive interests, and identified himself with many religious and benevolent enterprises. In the politics of that exciting period he took an intense interest, and was one of the few “Free Soilers”* of the town. He was a member of the convention that nominated their Presidential candidate in 1848, and was an ardent worker for human rights. Many colored fugitives found a helper in him, and his house a home, on their way to Canada. At this time he became a member of a Masonic lodge in Keene. He was also, as a “Son of Temperance,” active and successful in efforts to reclaim intemperate men and restrict the liquor traffic in Walpole.”

The house stands as a testament to both the architectural continuity and the moral courage of Walpole’s residents, preserving the physical and historical landscape of the village for the present day.

*The “Free Soilers” (1848-1854) were members of the mid-nineteenth-century Free Soil Party, a third-party movement focused on opposing slavery’s expansion into western U.S. territories, advocating for “Free Soil, Free Speech, Free Labor, and Free Men” and free land grants for settlers, eventually merging into the Republican Party.

Continue East on Middle Street to Main Street; turn Right (South)

25 Main Street — William Buffum House

Built around 1785 with a Georgian core, the William Buffum House was extensively remodeled in the 1830s into a striking Greek Revival residence by merchant William Buffum. Its most prominent features include a two-story Doric portico, a pedimented façade with a Palladian window, and Greek Revival door and window detailing, while much of the original Georgian structure remains visible on the north side. The house exemplifies Walpole’s architectural evolution, blending post-colonial craftsmanship with nineteenth-century aspirations, and remains a cornerstone of the village’s historic Main Street.